Reverse Proxy Deep Dive (Part 4): Why Load Balancing at Scale is Hard

This post is part of a series.

Part 1 - A deep dive into connection management challenges.

Part 2 - The nuances of HTTP parsing and why it’s harder than it looks.

Part 3 - The intricacies of service discovery.

Part 4 - Why Load Balancing at Scale is Hard.

Load Balancing

One of the most critical roles for a reverse proxy is load balancing requests across different upstream hosts. From a list of upstream servers, the proxy must decide where each incoming request should go.

One of the most critical roles for a reverse proxy is load balancing requests across different upstream hosts. From a list of upstream servers, the proxy must decide where each incoming request should go.

The primary goals of load balancing are:

- Optimal resource utilization: Evenly distribute load to maintain consistent performance and avoid hotspots.

- Resilience: Ensure that the failure of a single server doesn’t cause outsized impact on capacity or latency.

- Operational simplicity: Simplify capacity planning, monitoring, and failover by evenly balancing load.

Round-robin might work fine at small scale, but as systems grow, load balancing becomes far more complex due to many real-world challenges.

What Makes Load Balancing Harder at Scale

All Requests Are Not Equal

While round robin sends an equal number of requests to each host, it doesn’t account for how different those requests may be. In large systems:

- Some requests are read-heavy, others write-heavy.

- Some carry large payloads in the request, others in the response.

- Some are CPU-bound while others are IO-bound.

This disparity means that round robin can overload one server while leaving others underutilized.

Example: Imagine two types of requests: image uploads (large payloads, heavy compute) and profile lookups (lightweight reads). Sending equal numbers of each to all hosts can cause unpredictable load patterns.

Alternatives:

- Least Connections: Distributes requests to the host with the fewest active connections. This requires the proxy to maintain accurate connection tracking.

- Power of Two Choices (P2C): Randomly pick two hosts and send the request to the one with fewer active connections. A randomized algorithm but simple, fast, and surprisingly effective in various scenarios.

Custom Server Requirements

Some requests require stickiness to specific hosts due to:

- Caching effectiveness

- Session persistence

- Sharding (e.g., based on user ID)

Round robin fails here. One common strategy is hashing on a request property (like user ID), but this risks uneven load distribution.

Improvement:

- Use multi-level hashing or consistent hashing with virtual nodes to reduce imbalance while preserving routing guarantees.

Server List is Not Static

In dynamic environments, the list of upstream hosts is in constant flux due to deployments, auto-scaling, or node failures. Kubernetes further complicates this by frequently changing pod IPs. Even a simple restart can result in a new address, making upstream tracking more volatile and requiring robust discovery and update mechanisms.

Adding a Host

Challenges:

- Redistribution: Rebalancing load often requires shifting active connections, which can disrupt ongoing sessions and degrade user experience. This is especially problematic for long-lived connections, where preserving session affinity and cache locality matters. Protocols like gRPC and HTTP/2 amplify the issue, as they perform better with fewer, stable connections rather than frequent churn.

- Spikes: New hosts start with zero connections, so proxies often send them a disproportionate amount of traffic to catch up. This sudden spike can overwhelm the host, leading to degraded performance. Since latency and throughput often correlate directly with load, both the host and user experience suffer during this warm-up period.

- Warm-Up Needs: Some applications, especially those built in Java, need time to reach optimal performance after startup. If a proxy sends the same volume of traffic to a cold host as to a warmed-up one, it can lead to uneven resource usage and higher latency. To avoid this, proxies should gradually ramp traffic to new or restarted hosts.

Mitigations: To mitigate this, proxies can incorporate additional algorithms and techniques such as:

- Consistent hashing to minimize client reassignment during host changes or rebalancing.

- Slow Start to gradually ramp up traffic to new or recently recovered hosts, avoiding sudden overload

- Weighted load balancing (e.g., weighted round robin or weighted least connections) to assign traffic proportionally, allowing smoother integration of hosts with lower initial capacity.

Warm Up/Slow Start

Many Java-based services or those using heavy caching need warm-up time before handling peak load. This period varies by request type and service behavior, making a universal solution difficult. A common approach is to gradually ramp up traffic to new hosts using heuristics.

How Long Can a Host Handle Reduced Traffic?

Since capacity planning assumes each host handles a share of traffic, slow warm-up on some hosts shifts load to others, risking overload. Deployment strategies often account for temporary capacity drops. In phased or batched rollouts, the current batch must be ready to handle its share before the next one goes offline. This creates a natural upper limit on warm-up time.

Removing a Host

- Draining Strategy: For smoother shutdowns, upstream servers often provide a draining mechanism where they stop accepting new connections but continue serving existing ones for a while. Proxies must support this by keeping existing connections alive while excluding the draining host from load balancing for new requests. This typically involves a “half-open” or “half-closed” state, which adds complexity to proxy logic and connection management.

Global View vs Local View

In large-scale systems, proxy nodes operate independently, each with only a local view of the system. Their load balancing decisions are made in isolation, often without coordination or global state, which can lead to suboptimal traffic distribution and resource inefficiencies.

- When a new host is added, all proxies see it with zero connections. Each proxy independently tries to send enough traffic to balance the load, often causing a flood of new requests and a traffic spike.

- Similarly, when an upstream host degrades, each proxy detects it independently. This leads to slow convergence even when all requests to that host are failing. For example, if a proxy ejects a host after 3 failures, and you have 50 proxies, it may take 150 failed requests (or more) before the fleet stops sending traffic. This gets worse when the host is reintroduced after a fixed interval. If it’s still bad, another 150 requests can get blackholed. Envoy’s outlier detection works this way, and this method doesn’t scale well with large fleets

Mitigations: There are often complex mechanisms to handle these scenarios:

- Proxies use active health checks before bringing a bad host back into rotation. When a host is marked unhealthy through passive health checks or outlier detection, it is placed in a quarantine list. Before reintroducing it, active health checks verify the host’s readiness, reducing the chance of flooding it with bad requests again.

- Add jitter to health check schedules so that not all proxy nodes send checks simultaneously, preventing overwhelming a recovering host.

- Partition proxy fleets by assigning different subsets of proxies to specific upstream hosts. This limits the blast radius and improves control but requires complex coordination for deployment, subset assignment, and synchronization, making it challenging to implement correctly.

- Use server feedback such as headers or error codes to communicate overload conditions to proxies. Because upstream hosts have a complete view of their load, they can notify proxy nodes when they are overwhelmed and instruct them to reduce traffic accordingl

Proxy Architecture

Proxy architectures can amplify load balancing challenges, especially when handling concurrency on machines with many CPU cores. Some proxies do not share load balancing information across threads, even on the same host, which widens the gap between local and global views. Envoy is a notable example—running Envoy on servers with many threads (such as 64 cores) can make uneven load distribution more noticeable.

Shared vs Per-Thread View Proxies like Envoy use per-thread views to avoid cross-thread contention. While this improves efficiency, it reduces load balancing accuracy. On systems with many cores and low request rates, this can result in uneven load distribution.

Per-thread views also complicate sharing health checks and feedback between threads, potentially increasing error rates.

In contrast, HAProxy uses optimized data structures like ebtree to manage contention while maintaining a global view across threads, which improves load balancing precision.

Common load balancing algoithims and challenges

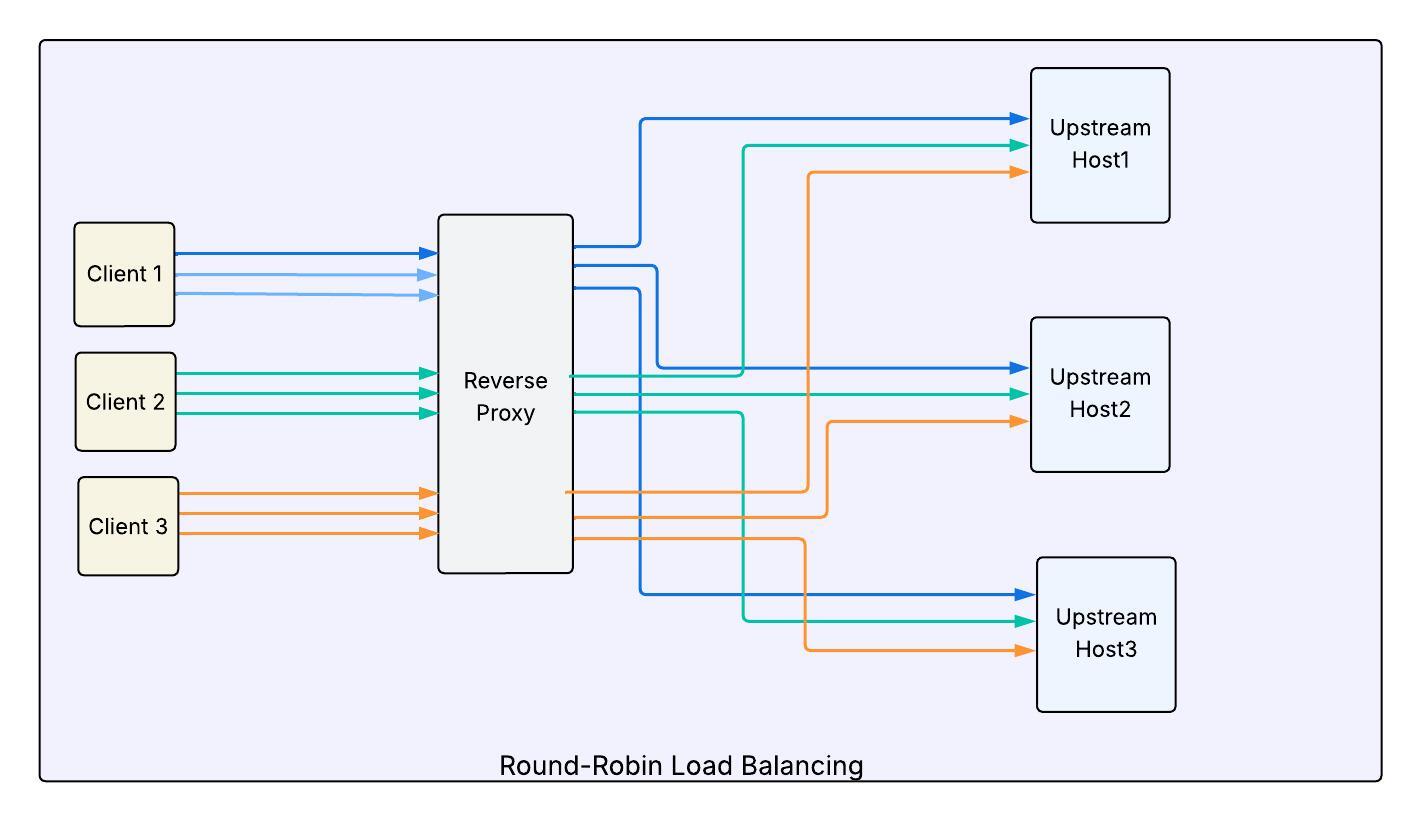

Round-Robin

In this approach, each request is sent to the next host in line. It is simple and fair, but only if all hosts are healthy, fully warmed up, and equally performant.

Challenges

-

Maintaining a consistent view

The proxy must keep a consistent view of the host list, which becomes tricky during deployments. Hosts are removed from rotation and later added back, but the order may differ. Sometimes, new hosts are entirely different from the previous ones, making consistency hard to maintain. -

No warm-up phase

When new hosts are added, they begin receiving traffic right away, even if they are not yet fully initialized or ready to handle the load. -

Unequal request types

Not all requests are the same. Some are CPU-intensive, others take longer to process, and some are very lightweight. If traffic is distributed purely by request count, it can lead to imbalanced load—overloading some nodes while underutilizing others.

Typically, load balancers implement a basic enhancement of weighted round robin to address the static nature of the original algorithm.

Least Connections

The proxy sends requests to the host with the fewest active connections. This accounts for variable load per request, such as long-lived versus short-lived calls.

Challenges

-

Burst traffic When a new node is added, it naturally has the fewest connections and starts receiving a disproportionate share of traffic. Since new connections can be expensive (e.g., due to TLS setup), this sudden spike can overwhelm the server, especially if it is not yet warmed up.

-

More work for proxy The proxy must track all open connections, which adds operational complexity.

Consistent hashing

This strategy is useful when requests with certain properties should consistently go to the same upstream host. It’s often used to improve cache hit rates or maintain session persistence. The proxy applies a hash function on a specific request attribute (like user ID or session ID) to pick a host.

Challenges

-

uneven distribution Request volume and cost can vary based on the hashed property. For example, one user might generate significantly more traffic or make heavier API calls than another. This can overload some hosts while leaving others underused. One common mitigation is to apply consistent hashing only to request types that are more uniform in cost or volume, like payment or messaging APIs, and to use a property that is known to be evenly distributed.

-

Burst traffic Adding new nodes can cause traffic to shift abruptly, leading to bursts that may overload the new host.

Random Choice of Two

Although it sounds counterintuitive, using randomness can lead to surprisingly good load balancing. In this approach, the proxy picks two random hosts and selects the one with fewer active connections. This method works well at scale and handles varied load types effectively, including long-lived, slow, or bursty requests.

Challenges

-

No warm-up phase Like other strategies, this approach does not solve the problem of cold starts. New hosts may still receive traffic before they are fully ready.

-

Added complexity The proxy must perform additional operations for random selection and comparison. However, the performance gain often justifies the cost.

Final Thoughts

On paper, load balancing looks simple. Round robin feels like the obvious choice. In practice, creating an effective load balancing algorithm is hard and often relies on heuristics. Modern infrastructure, which is dynamic, elastic, and ephemeral, makes this even more challenging.

A reverse proxy is expected to:

- Keep up with a rapidly changing view of the system and track changes accurately

- Balance load effectively while respecting the limitations of upstream servers

- Anticipate failures and isolate their impact

- Do all of this while consuming as few resources as possible

All of this has to be done while operating with partial information, uneven data, and strict performance limits, conditions that turn load balancing into a surprisingly difficult problem.

What’s Next

This series has been a long journey. The next post will be the last and will cover the remaining complexities, including connection pooling, TLS reuse, retry logic, and why this layer can often be a hidden source of bugs and latency.

This post is part of a series.

Part 1 - A deep dive into connection management challenges.

Part 2 - The nuances of HTTP parsing and why it’s harder than it looks.

Part 3 - The intricacies of service discovery.

Part 4 - Why Load Balancing at Scale is Hard.