Reverse Proxy Deep Dive (Part 1): The Complexity of Connection Handling

This post is part of a series.

Part 1 - A deep dive into connection management challenges.

Part 2 - The nuances of HTTP parsing and why it’s harder than it looks.

Part 3 - The intricacies of service discovery.

Part 4 - Why Load Balancing at Scale is Hard.

A Deep Dive into Reverse Proxy

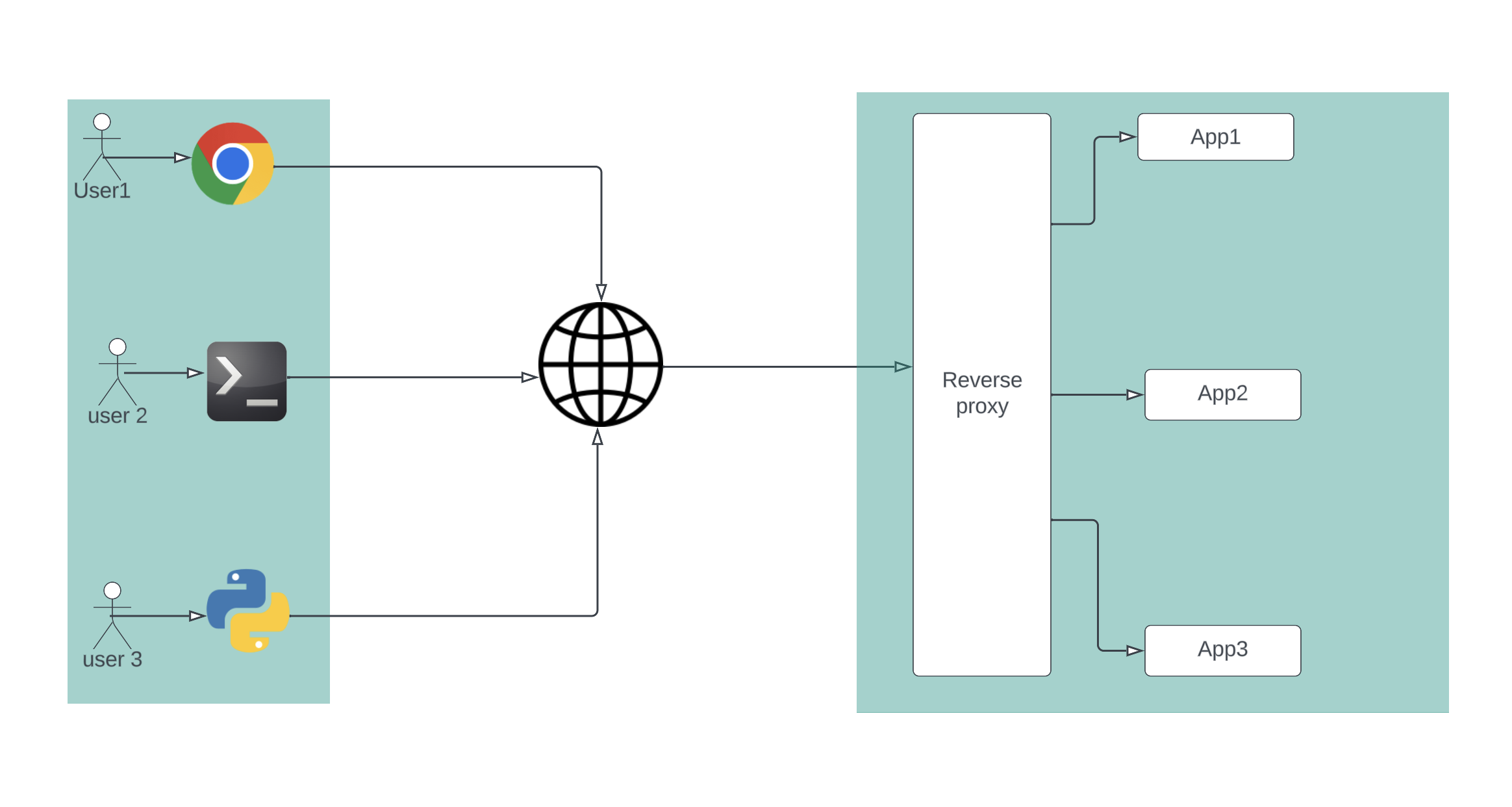

A reverse proxy is a critical piece of software commonly found in various setups within a distributed system. You may have encountered it as a proxy enabling service mesh, a load balancer distributing the load among different database instances, or an edge proxy hiding the complexity behind a site.

Several excellent reverse proxies exist, such as HAProxy, Nginx, Envoy, Caddy, Traefik, Zuul, Apache Traffic Server, etc. Each has its strengths and weaknesses, often used in specific contexts. For service mesh, Envoy/Linkerd are common choices, while for edge proxy, Nginx/HAProxy are preferred. For caching proxy, ATS is a great option, and HAProxy shines in load balancing among different database instances.

Unveiling the Functions and Intricacies of Reverse Proxies

At its core, the reverse proxy facilitates communication between clients and origin hosts. The high-level workflow involves:

- Clients connecting to the reverse proxy

- Client sending requests (HTTP/TCP/UDP/SSH, etc.)

- The proxy forwarding the request to one of the origin hosts

- Proxy awaiting the response from the origin

- Proxy forwarding the response to the client

- Proxy/client/origin closing the connections.

Note: For simplicity, we’ll focus on Layer 7 (HTTP) reverse proxy.

Breaking down the workflow reveals several essential functionalities:

- Connection Management:

- Listening to ports

- Accepting connections

- Accepting HTTP requests

- HTTP Request Parsing/Header Manipulation:

- Parsing HTTP requests

- Sanitizing requests

- Manipulating headers

- Rewriting paths, etc.

- Service Discovery/Downstream Discovery:

- Identifying valid hosts for handling requests

- Identifying one host as the target for specific requests

- Functioning as an HTTP Client:

- Initiating connections to origin hosts

- Sending to the origins

- Accepting responses from the origin

- Observability:

- Visualizing activities at the proxy tier to understand what’s going on.

Each of these steps is complex, and a deeper dive into each is warranted.

Deep Dive into Connection Management

On a high level, the proxy needs to bind to a specific port, listen on it, wait for data, read/process received data, forward data to the origin, receive data from the origin, and write it back to the connection for clients to read the response. This process continues in a loop.

Standard programming languages provide network libraries for writing a simple server with a workflow like:

1. Create a TCP socket

2. Bind to a specific port

3. Listen on the port/wait for connection request

4. Accept the connection and be ready for data transfer

5. Read/process incoming data

6. Repeat step 5 until the connection needs to be closed based on some application logic

7. Close the connection

What Makes It Complex

Concurrency

By default, socket/network I/O is blocking. The mentioned code works well for one client, but with multiple clients, handling concurrency becomes crucial. One way is to use one thread for each client connection. However, beyond a few hundred clients, the cost of creating threads and getting blocked becomes inefficient.

Non blocing IO and I/O multiplexing

This led to the emergence of non-blocking I/O as a solution. The idea here is that if an I/O is not ready for read/write, instead of blocking the thread, it can simply respond with error/notification. In linux, passing an extra parameter O_NONBLOCK will put the file decriptor in nonblocking mode.

From the man page of socket

It is possible to do nonblocking I/O on sockets by setting the O_NONBLOCK flag

on a socket file descriptor using fcntl(2). Then all operations that would

block will (usually) return with EAGAIN (operation should be retried later); connect(2) will return EINPROGRESS error.

This resulted in strategies such as polling. A thread periodically polls the network socket/I/O to check if it’s ready/has data to process. If not, then it sleeps for some time and repeats the process. This way, busy wait was reduced, and threads/processes could scale up to a few hundred concurrent requests.

A possible optimization is to create multiple processes, and each process handles a few threads.

Apache http server is one example where they use this hybrid model. Again, this works for a few thousand clients but doesn’t scale beyond that. Periodically checking hundreds/thousands of connections/file descriptors (fd) for I/O readiness is still quite costly.

To optimize further, what if instead of clients checking for each of these fds independently, if there is some way for clients to list all fds they are interested in and be notified when they/some are ready.

I/O multiplexing: Select, Poll and epoll

Linux provides a few system calls for the same purpose: select and poll. With select, we can provide a list of fds and three arrays of bitmasks corresponding to read/write/error readiness, respectively. This allows us to monitor multiple fds simultaneously.

Poll is similar but slightly more efficient and uses a single array for watching events instead of three separate arrays.

reference: select-vs-poll-vs-epollI

With select/poll, we can handle a few hundred/thousand connections, but at a higher scale, this is also not sufficient.

A further optimization to this approach is the epoll system call. Instead of linearly going through each of the fds (think in tens of thousands of them) to identify which one is ready, we get a list of fds that are ready.

performance: select & poll vs epoll

# operations | poll | select | epoll

10 | 0.61 | 0.73 | 0.41

100 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 0.42

1000 | 35 | 35 | 0.53

10000 | 990 | 930 | 0.66

C10K and the event driven architecture

In the late ’90s, the difficulty of handling a very large number of concurrent clients dominated networking discussions and led to the term called the C10k problem, where the goal was to handle 10k concurrent connections from the same host.

This resulted in another architectural paradigm called event driven programming.

The concept revolves around employing a single event loop, rather than generating a thread/process for each connection. This central event loop actively monitors I/O-ready file descriptors (fds) and signals specific worker threads to handle the actual requests. The core event loop is designed to be lightweight, focusing solely on overseeing the I/O readiness and informing the dedicated worker thread to process the respective requests. Consequently, this design allows the software to scale autonomously, regardless of the number of connections.

NodeJs event loop is a great example. Other examples are Java Netty, C libevent.

1. Event-Driven Programming

2. Multiplexing I/O Operations

3. Thread Pooling

4. Networking and OS Optimizations

Event-driven architecture worked very well for a long time, but it has its own limitations. One of the biggest limitations is that it’s single-threaded. So, if there is a blocking operation, it will block the entire event loop. This poses a significant problem for long-running operations such as TLS handshake. Consequently, this issue led to the development of multi-threaded event loops.

The End of Moore’s Law and the Rise of Multiple Cores

With the demise of Moore’s law multiple cores have become the norm, and it’s very common to have a large number, such as 32, 64, or even larger numbers of cores.

Different proxies use different strategies to address this. HAProxy (version below 1.8) used to have multiple processes to handle this scenario, and the same applied to NGINX, which uses a multi-process model.

While this works well and performs much better than the single-threaded event loop, it does create a lot of overhead to deal with multiple processes, especially around config management, log aggregation, load balancing efficiency, and connection management.

Socket Sharding

Socket sharding is another interesting feature used by proxies to leverage os’s load balancing feature.

SO_REUSEPORT can be used with both TCP and UDP sockets. With TCP sockets,

it allows multiple listening sockets—normally each in a different thread—to

be bound to the same port. Each thread can then accept incoming connections

on the port by calling accept(). This presents an alternative to the

traditional approaches used by multithreaded servers that accept incoming

connections on a single socket.

Envoy uses this feature to bind each listener thread to the same port and effectively utilizes the kernel-provided load balancing to distribute the load among multiple threads.

So, on the listening side, it is able to scale very well. However, this suffers from load balancing/connection management issues. Envoy prefers to perform end-to-end request processing in the same thread, and each thread is unaware of how other threads are processing the requests. So, if you have a lot of cores and a lot of origins (upstream in Envoy’s terms), the load balancing could be very skewed, and you may end up with more connections to the origin.

This is not a big problem for a sidecar where you typically allocate only a few cores to the sidecar

Nginx > 1.9.1 support this socket sharding as well.

HAProxy (>= 1.8) enabled multi threading as well but took slightly different approach

HAProxy multi threading support

Instead of having one thread for the scheduler and a number of threads for the

workers, we have decided to run a scheduler in every thread. This has allowed

the proven, high-performance, event-driven engine component of HAProxy to

run per thread and to remain essentially unchanged.

Additionally, in this way, the multithreading behavior was made very similar

to the multiprocess one as far as usage is concerned, but it comes without

the multiprocess limitations!

While some of these optimizatin are good for handling cores upto 64, beyond that it becomes further complicated. HAproxy intriduced this concept of thread group to scale it upto 4096 cores

A thread group, which you create with the thread-group directive in the global

section of your configuration, lets you assign a range of threads, for example

1-64, to a group and then use that group on a bind line in your configuration.

You can define up to 64 groups of 64 threads.

In addition to taking better advantage of available threads, thread groups help

to limit the number of threads that compete to handle incoming connections,

thereby reducing contention.

Further challenges in connection managment

Things become further complicated when we want to support TLS. So, we not only need to establish the TCP connection, but we also need to handle the TLS handshake and all the complexity involved. This raises several questions, such as which TLS library to use: OpenSSL, libessl, or BoringSSL. None of these is a drop-in replacement for the others, adding some complexity. One way to simplify is just to stick to one library, but the challenge is that we’ll also be bound by its limitations. e.g. from Boring ssl’s home page

Although BoringSSL is an open source project, it is not intended for general

use, as OpenSSL is. We don't recommend that third parties depend upon it.

Doing so is likely to be frustrating because there are no guarantees of API

or ABI stability.

What if we need to support different TLS levels like TLS 1.1, 1.2, or 1.3?

Another significant challenge is what if we also need to support different protocols like UDP?

How about triggering timeouts and dealing with abusive clients?

Conclusion

While connection management is very basic and fundamental, making it work at a very large scale is quite challenging and requires specialized handling. Each of the popular proxies has employed multiple techniques to scale it for their use cases, and each has its own pros and cons. Make sure you understand it well before choosing one over the other.

This post is already too long; the rest of the complexity related to the reverse proxy (HTTP parsing, service discovery/load balancing, HTTP client, and observability) will be discussed in subsequent posts.

This post is part of a series.

Part 1 - A deep dive into connection management challenges.

Part 2 - The nuances of HTTP parsing and why it’s harder than it looks.

Part 3 - The intricacies of service discovery.

Part 4 - Why Load Balancing at Scale is Hard.