Reverse Proxy Deep Dive (Part 3): The Hidden Complexity of Service Discovery

This post is part of a series.

Part 1 - A deep dive into connection management challenges.

Part 2 - The nuances of HTTP parsing and why it’s harder than it looks.

Part 3 - The intricacies of service discovery.

Part 4 - Why Load Balancing at Scale is Hard.

What Is Service Discovery?

At its core, the job sounds simple:

- Maintain an up-to-date list of upstream hosts

- Remove bad hosts from rotation as quickly as possible

But doing this accurately and efficiently across thousands of services, tens of thousands of hosts, and a constantly shifting topology turns service discovery into one of the most challenging parts of building a robust proxy.

Goals and Constraints of Service Discovery

An effective service discovery system should strive to meet the following goals:

- Timely updates: Quickly identify changes in the host list to optimize resource use. Delays lead to waste and can hurt capacity.

- Fast failure detection: Detect and remove bad hosts promptly to avoid blackholed requests and degraded user experience. This is often more urgent than adding new hosts.

- Efficiency: Minimize the resource and operational cost of maintaining the discovery system.

- Simplicity: Failures will happen, and simpler systems are easier to debug and fix under pressure.

In the following sections, we’ll explore various approaches to service discovery, the challenges they face, and how these constraints influence the suitability of each approach in different environments.

Ways to Discover Hosts

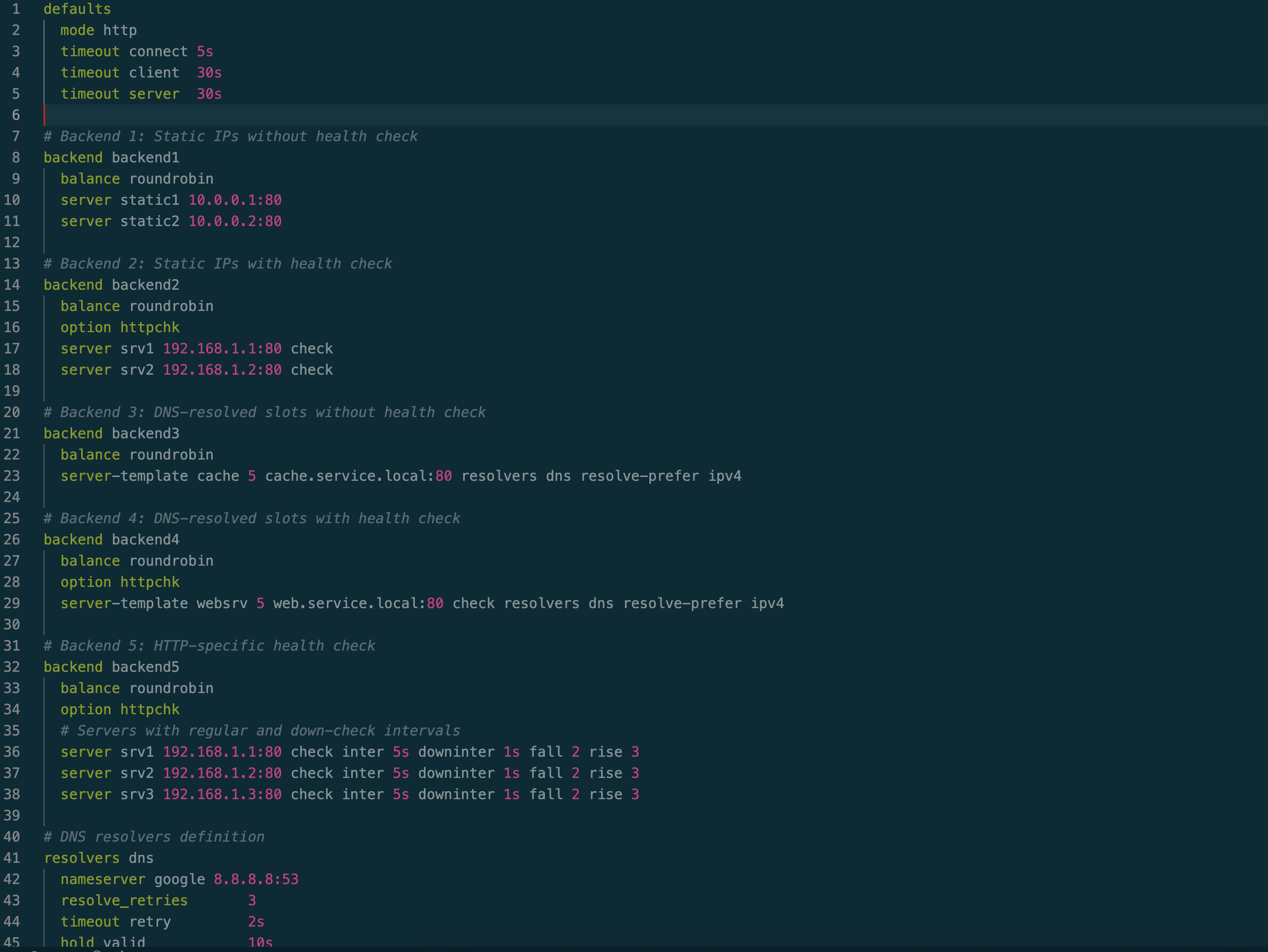

HAProxy config showing static ip, dns slots, health-check, health-check with different frequency

HAProxy config showing static ip, dns slots, health-check, health-check with different frequency

HAProxy Config Example Github gist

1. Static Host Lists

This is the most basic form of service discovery. IPs or hostnames are hardcoded into the proxy configuration. It works well in environments where the infrastructure remains relatively static, such as dedicated on-premises clusters with minimal host churn.

When combined with health checks, this approach becomes quite robust and can tolerate occasional upstream host or application failures. While it effectively removes failing hosts from rotation, it doesn’t handle adding new hosts in rotation without restart.

A small readability improvement is using hostnames instead of IPs. Proxies typically resolve hostnames to IPs at startup using OS libraries like glibc.

Pros:

- Simple and predictable

- No external dependencies

- Highly efficient

- Quickly removes bad hosts from rotation when paired with health checks

Cons:

- Not dynamic

- Requires restarts to add new hosts

- Restarts can disrupt long-lived connections, so draining is needed before switching. This adds complexity and potential for user impact.

For systems with fixed capacity planning, low traffic, and no need for dozens of proxy nodes, this approach can be a strong fit.

Challenges at Scale

- Health checks can create excessive load as the number of proxy nodes grows. Without shared state, they may cause storms that overwhelm upstream hosts.

- Health checks also consume significant proxy resources. To stay accurate and reliable, they must run frequently, leading to rapid resource depletion at scale

2. DNS-Based Discovery

Once DNS is configured, it can be used for service discovery by grouping all upstream hosts under a single FQDN. The proxy resolves this FQDN to obtain the list of IP addresses for those hosts and can dynamically update the host list by performing DNS queries directly.

We can offload health checks to the DNS ecosystem, reducing the load on the proxy. This decouples proxy scaling from health check concerns. By sharing state and sharding upstream hosts intelligently, we can optimize health check traffic and resource usage, independent of proxy scale.

DNS-based resolution is better for dynamic workload, but it adds overhead. The proxy must:

- Parse DNS records, often mixing IPv4/IPv6

- Handle reordering (most DNS clients shuffle the host list)

- Diff the result vs existing list and identify the delta

- Remove stale entries, shut down old connections

- Add new entries into the rotation

This gets worse when the host list is large (say, 200+ entries). If the algorithm isn’t efficient, even something as simple as diffing host lists can become a bottleneck. HAProxy had encountered challenges with this in the past.

Most DNS traffic relies on UDP, which has a strict packet size limit, 512 bytes for traditional and 4096 bytes with EDNS(0). If the response exceeds that limit, it gets truncated. Then we need to retry over TCP, but even TCP has a limit (65,535 bytes) on how many records it can return.

This means the proxy now has to fully implement both DNS-over-UDP and DNS-over-TCP, just to get a list of hosts.

Another key concept in DNS based system is DNS Time To Live

DNS TTL Tradeoffs

DNS TTL determines how long the proxy should treat the resolved host list as fresh.

High TTL

- Fewer DNS lookups

- Lower CPU and memory overhead in the proxy

- Less churn in connection pools

But:

- Hosts may go down, drain, or be replaced without the proxy knowing

- Traffic may continue flowing to broken nodes

Low TTL

- More up-to-date host list

- Dead hosts removed faster

But:

- High cost from frequent DNS queries, parsing, and memory updates

- Adds latency, especially with large upstream lists

Hybrid Approach

Use DNS for discovery combined with health-checks to prune bad hosts locally.

- On each DNS update, fetch the full list

- Periodically run health-checks on each host (HTTP or TCP probes)

- Temporarily remove failing nodes

- Let DNS eventually catch up and remove bad entries

It is a balance: reduce reliance on fast TTL but do not blindly trust DNS alone.

We will cover health-checks in more detail later in the health-check section.

Pros:

- Supports dynamic workloads

- Simple to set up; DNS is a well-understood system

- Leverages existing DNS infrastructure, minimizing new dependencies

- Efficient when combined with smart health checks

Cons:

- Integrating DNS into the proxy adds complexity in the proxy and can increase resource usage

- DNS updates may have delays when adding new hosts

- DNS size limits impose design constraints

In systems operating at moderate scale, with frequent but manageable changes and tolerance for some delay in host updates, this approach offers a strong balance between simplicity and flexibility.

Challenges at Scale

- Offloading health checks to DNS reduces proxy burden but doesn’t fully solve the issue

- Rapid updates can strain the DNS system and introduce instability

- Lacks support for app-specific needs like slow starts or custom traffic ramp-up strategies

3. External Discovery Systems

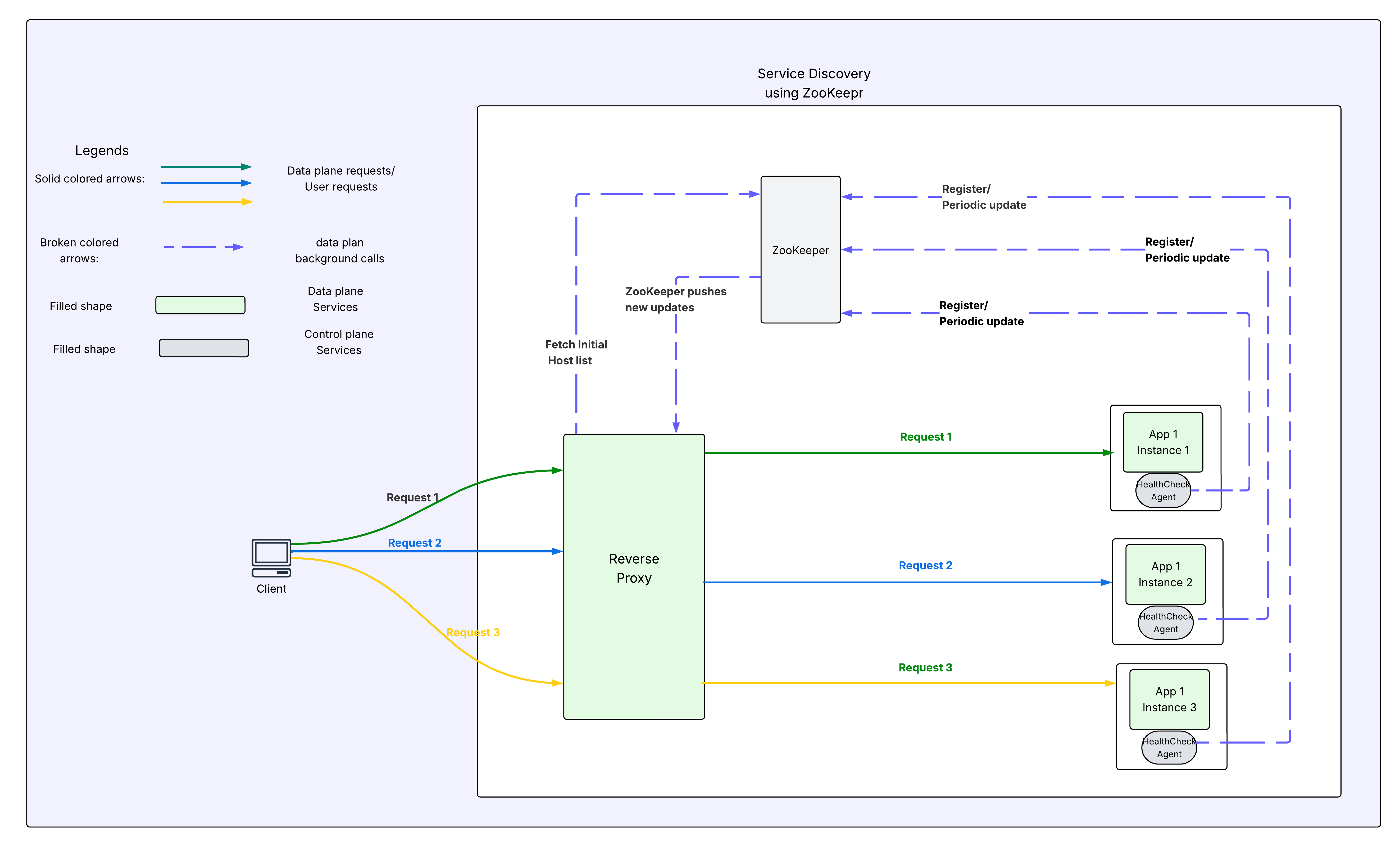

Service Discovery Using ZooKeeper

Service Discovery Using ZooKeeper

When DNS isn’t good enough, large systems build their own discovery control planes, often using:

- ZooKeeper (classic choice for strongly consistent registries). Examples: Pinterest, Linkedin

- HTTP/gRPC APIs (e.g. Envoy’s xDS)

- Runtime API + external sync agents (like HAProxy’s socket API)

Most modern systems address DNS limitations through several techniques:

- Using richer transport protocols (like TCP or HTTP) to bypass DNS size limits.

- Embedding additional metadata (e.g., health status, locality, slow start needs) to support app- or system-specific behaviors.

- Adopting agent-based models, where apps or hosts directly register with a central system, eliminating the need for periodic health checks and preventing health check storms.

- Pushing updates only on change, reducing unnecessary polling and minimizing proxy CPU/memory usage.

Example: ZooKeeper-style Architecture

- Each application either embeds a client thread or runs a sidecar agent that registers itself with ZooKeeper when it starts.

- This registration is maintained via heartbeats. If the heartbeat stops or the connection is lost, ZooKeeper automatically removes the host and notifies subscribers.

- Proxies initialize by querying ZooKeeper for the current host list and set a watch for changes.

- A persistent connection to ZooKeeper is maintained for ongoing updates.

- When a change occurs (e.g., a host added or removed), the proxy receives a notification and refreshes the host list.

- If the connection breaks, the proxy re-establishes it and re-syncs the host data.

This approach significantly reduces the overhead of periodic health checks and enables faster, more efficient updates.

Pros:

- Faster updates

- No/minimal overhead of health-checks

- Works with large scale system and doesn’t suffer DNS size limits

Cons:

- Integration is custom (many proxies don’t natively support ZooKeeper). Building TCP level protocols are much harder.

- Dependency on a new system like ZooKeeper, Which comes with its own operational and resource challenges

- These systems often favor strong consistency, which can hurt availability under load

- Delete events require the proxy to re-fetch and compare.

- Agent model also adds additional resource overhead and sometimes can cause trouble if that ecosystem has problem

Envoy’s xDS takes this approach further by

- Favoring eventual consistency over strong consistency for such updates

- Leverages gRPC for transport. A good gRPC client simplifies some of the tcp level challenges and better abstractions to work with.

health-check

While service discovery helps build a list of healthy nodes for routing traffic, its source of truth is not always up to date. This can happen for many reasons, such as network partitions, the high cost of health-checks at the DNS layer, broken health-check setups, misbehaving components in the ecosystem, or temporary unavailability of the service.

Although the goal is to make service discovery as accurate as possible and remove bad hosts quickly, achieving that level of precision is a difficult problem.

To guard against such scenarios, proxies often perform their own health-checks as a fallback.

Active Health Checks

The proxy periodically probes each host, typically with a simple HTTP or TCP request, to confirm it’s alive. Seems simple in theory, but expensive in practice:

- Thousands of hosts mean thousands of probes

- At scale, this burns CPU and network, especially if checks involve HTTPS or TLS handshakes

- Load spikes can happen if all proxies check all hosts at the same time

To reduce cost, many systems perform lightweight HTTP checks regularly and heavier HTTPS checks less frequently, such as one out of every fifty probes.

Passive Health Checks

Instead of probing, the proxy watches live traffic. If a host consistently returns errors or times out, it is marked as unhealthy.

Passive checks are cheap, but reactive. They only trigger after enough failures happen. Most systems combine both approaches, tuning frequency and aggressiveness based on traffic shape and failure patterns.

Final Thoughts

On paper, service discovery sound like a solved problem. In practice, this is a moving target, especially in dynamic environments with autoscaling, frequent deploys, and partial failures.

A reverse proxy is expected to:

- Keep up with a rapidly changing view of the world

- Detect and recover from bad hosts quickly

- Operate reliably at scale, under pressure, with minimal or no downtime

- Do all of this while consuming as few resources as possible

And it must accomplish this with limited visibility, inconsistent inputs, and tight performance constraints. That’s what makes service discovery deceptively hard.

What’s Next

In the next part of this series, we’ll look at load balancing, how proxies operate as HTTP clients. We will dive into connection pooling, TLS reuse, retry logic, and why this layer can be the silent source of bugs and latency.

This post is part of a series.

Part 1 - A deep dive into connection management challenges.

Part 2 - The nuances of HTTP parsing and why it’s harder than it looks.

Part 3 - The intricacies of service discovery.

Part 4 - Why Load Balancing at Scale is Hard.