Reverse Proxy Deep Dive (Part 2): Why HTTP Parsing at the Edge Is Harder Than It Looks

This post is part of a series.

Part 1 - A deep dive into connection management challenges.

Part 2 - The nuances of HTTP parsing and why it’s harder than it looks.

Part 3 - The intricacies of service discovery.

Part 4 - Why Load Balancing at Scale is Hard.

Deep Dive into HTTP Handling

At a high level, the HTTP workflow from a proxy’s perspective might seem straightforward:

- Receive the request from the client

- Parse and sanitize the request

- Uses different requst metadata (path, headers, cookies) to select an upstream host

- Manipulates the requests as needed

- Send the request to the selected upstream

- Read the response from the upstream

- Sanitize the response

- Forward response to the client

While many standard libraries support these steps, making them work reliably at scale, and meeting strict security and compliance requirements, is surprisingly complex. From malformed requests and malicious attacks to browser quirks, this layer becomes a battleground for performance, correctness, and resilience.

What Makes It Complex

Challenges in HTTP parsing

The Evolution of the HTTP Protocol

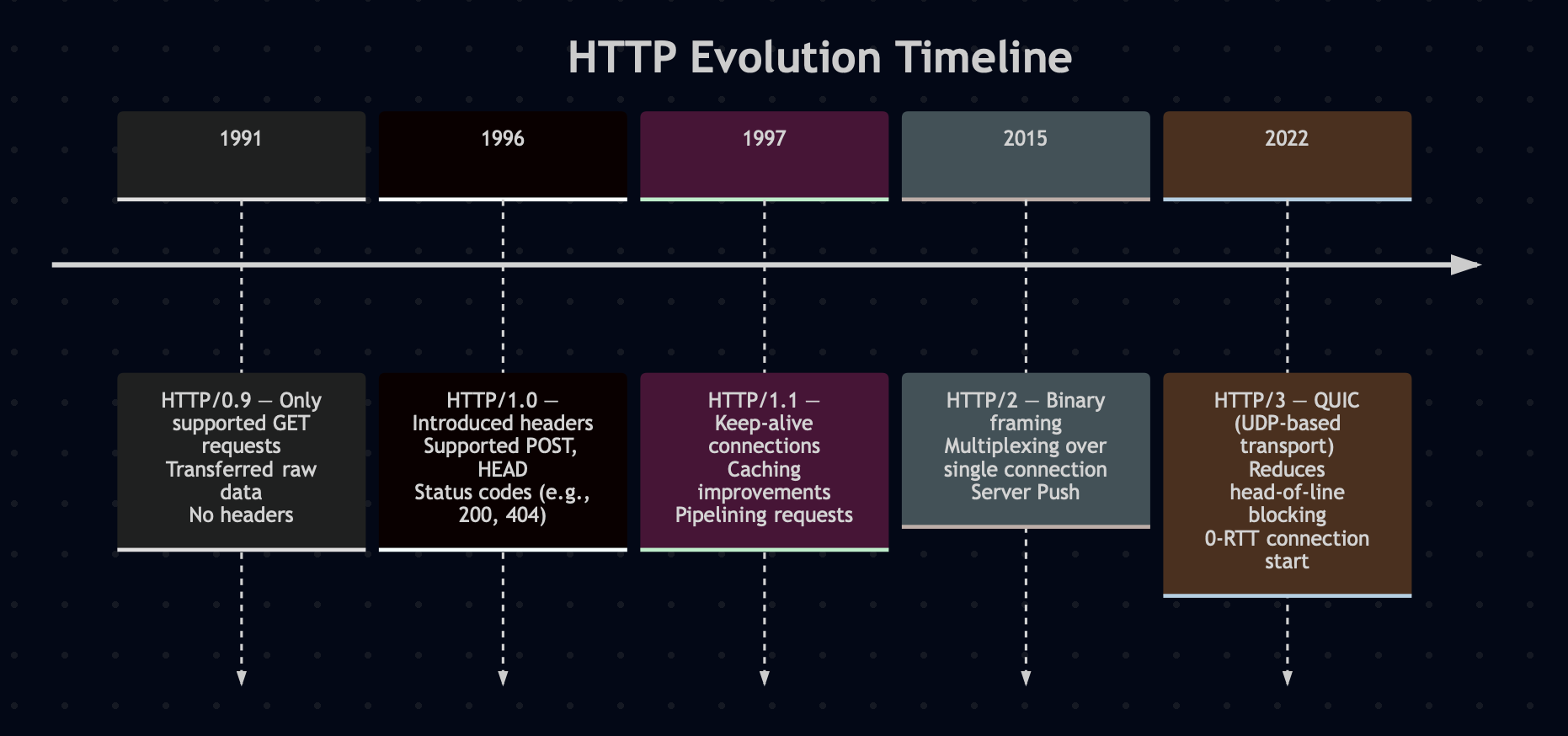

Over the years, http spec has significantly evolved. It started with simple request lines like GET /index.html in HTTP/0.9, moved to newline-separated headers and persistent connections in HTTP/1.1, and later adopted full binary framing and multiplexing in HTTP/2.

Each new version brought added features, redefined earlier assumptions, and introduced additional complexity. These changes require continual updates to existing systems, libraries, and tooling.

MDN offers a detailed exploration of HTTP’s evolution for those interested in a deeper dive.

Different Development Lifecycles of Clients, Proxies, and Servers

Clients and servers are often developed using different languages, frameworks, and platforms, each with their own independent lifecycles. Some systems, like in-car music players, may remain in use for 15 years or more, while clients and proxies evolve more rapidly. This disparity places the responsibility on the proxy layer to act as an intermediary, managing compatibility between components. The proxy often must decide which parts of the RFC specifications to enforce strictly and where to allow flexibility.

Examples include:

- According to the HTTP/1.1 specification, header names are case-insensitive. However, some clients and servers expect header names in a specific case. Reverse proxies typically provide a way to preserve or normalize casing. For instance, Haproxy provides a case option for preserving case and Envoy provides similar functionality.

- HAProxy has an option to accept invalid requests using accept-unsafe-violations-in-http.

Performance Considerations: One Size Doesn’t Fit All

Not all requests are the same. Some are small, while others carry large payloads. Some include long URLs or large cookies, while others do not. These variations make it difficult for proxy developers to create a single, highly efficient logic that works well in all cases. As a result, proxies often need to provide flexible configuration options and write code that can adapt to different traffic profiles.

These profiles can sometimes be in conflict. For example, supporting large header sizes requires more memory to parse and process incoming requests. At high throughput, this leads to increased memory usage and can affect overall system performance. This creates a trade-off between request size, memory consumption, and throughput.

Lack of Industry-Wide Standards for Key Limits

Limits like maximum URL length, cookie size, and header size vary widely across platforms, and in some cases, the default settings provided by frameworks or servers are surprisingly low or outdated.

Azure Front Door imposes the following limits on URL and query size:

Maximum URL size — 8,192 bytes — Specifies maximum length of the raw URL

(scheme + hostname + port + path + query string of the URL)

Maximum Query String size — 4,096 bytes — Specifies the maximum length of

the query string, in bytes.

Maximum HTTP response header size from health probe URL — 4,096 bytes —

Specified the maximum length of all the response headers of health probes.

Past investigations into cookie size reveal similar inconsistencies

Google Chrome — 4096 bytes

Internet Explorer — 5117 bytes

Firefox — 4097 bytes

Microsoft Edge — 4097 bytes

Typically, the following are allowed:

300 cookies in total

4096 bytes per cookie

20 cookies per domain

81920 bytes per domain

Handling quotes in Set-Cookie headers, whether single, double, or escaped, adds another layer of confusion. Some libraries interpret them strictly, others ignore them, and a few may even fail altogether. This inconsistency often leads to subtle bugs or broken behavior across browsers and frameworks. Here’s a great read on the challenges of cookie handling and how it impacts major websites.

Security: The Proxy Is the First Line of Defense

Even with established standards and defined behaviors, there are always bad actors who exploit gaps to try to break the system. Proxies deployed at the edge are particularly exposed to such clients and must be prepared to handle these cases with extreme caution.

Examples include:

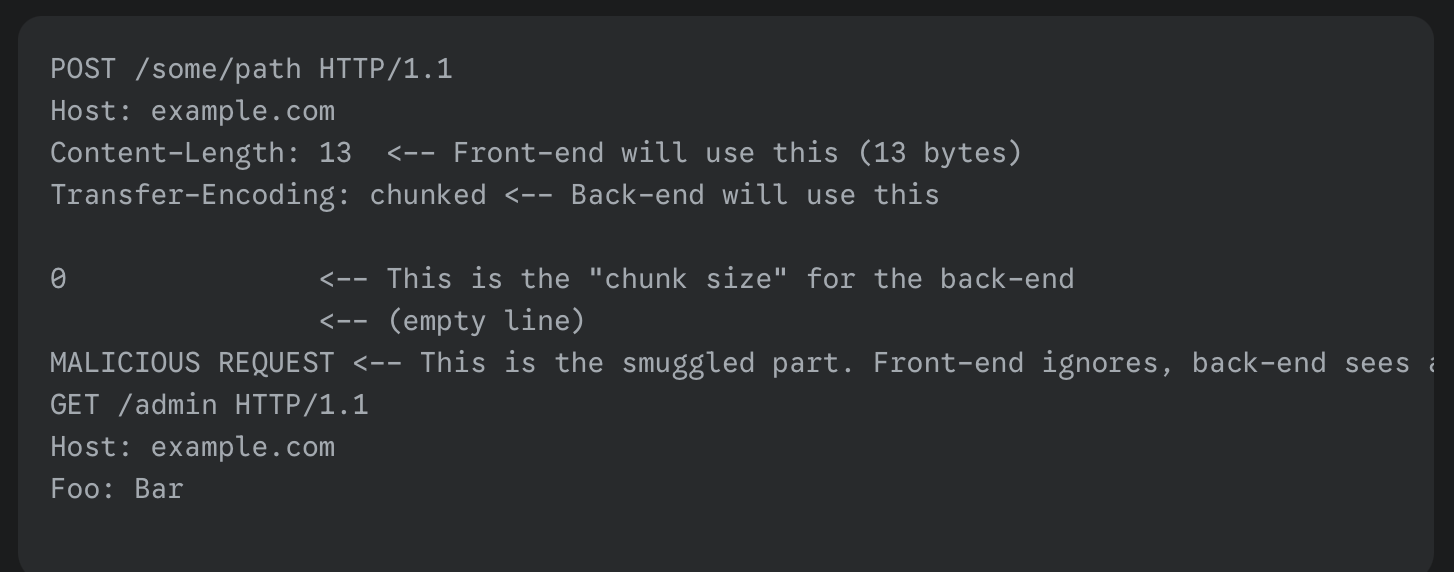

- Carefully crafted requests with conflicting Content-Length and Transfer-Encoding headers that can lead to HTTP request smuggling.

- Invalid http version like 0.5 can cause some servers to misbehave

- A well crafted user agent can lead to denial of service

Request Sanitization

Sanitizing incoming requests is critical for maintaining the stability, security, and performance of a proxy system. It involves more than basic filtering. Proxies need to detect malformed headers, incomplete or oversized requests, and block unwanted paths. This adds complexity and requires extra logic, memory, and CPU. Proxies must handle all of this while still performing well under pressure. Some examples include:

Validity Checks: Ensure the request conforms to protocol expectations. For example, reject requests with multiple Content-Length headers or conflicting Content-Length and Transfer-Encoding values.

Completeness: Attackers may send data very slowly to tie up resources (e.g., Slowloris-style). Proxies often enforce timeouts and request completion checks.

Size Limits: Reject requests that exceed acceptable limits for URL length, headers, or cookie size to prevent resource exhaustion.

Access Control: Block access to restricted endpoints such as /admin, /healthcheck, or any routes intended only for internal or localhost use. In many cases, servers are often configured to only accept requests from specific IP ranges. For example, if your static assets are hosted on a CDN, your origin server might expect occasional requests from the CDN’s IPs to refresh or preload content.

These endpoints should be accessible only by the CDN, and any requests from outside those trusted IP ranges should be blocked. This helps prevent abuse and ensures that internal or privileged endpoints are not exposed to the public internet.

Proxies can enforce these IP range checks early, adding a layer of security before the request reaches the application.

Response Sanitization

Similarly, outbound responses from the proxy also need to be sanitized. For example, the proxy often acts as a central enforcement point for GDPR compliance by ensuring only approved cookies are included in the response. It also plays a key role in setting appropriate security headers like Content-Security-Policy to protect clients from common web threats.

Header Manipulation

Reverse proxies often need to add/remove/update headers:

- X-Forwarded-For: Track client IP

- User-Agent: Normalize or drop broken values

- Geo-IP headers: For localization

- Request-ID: For observability

- Authorization: Normalize for downstream

Adding or removing headers requires the proxy to modify the incoming data stream before forwarding it. This typically means storing the full headers in memory, making them easy to inspect and update.

However, this introduces constraints on memory usage, limits on the maximum header size the proxy can handle, and other performance-related optimizations. One common optimization is to convert all header keys to lowercase to simplify lookups and configuration. While HTTP header names are case-insensitive per the spec, this normalization can occasionally cause issues with non-compliant clients or servers.

The User-Agent header is one of the most commonly used HTTP headers to identify the client making the request. It’s especially useful for detecting whether the client is a browser, mobile device, tablet (like an iPad), or other platform—allowing applications to adjust rendering or behavior accordingly. It is also useful for detecting whether a web crawler is accessing the site.

Examples

- iPhone User-Agent:

Mozilla/5.0 (iPhone; CPU iPhone OS 16_6 like Mac OS X) AppleWebKit/605.1.15 (KHTML, like Gecko) Version/16.6 Mobile/15E148 Safari/604.1 - iPad User-Agent:

Mozilla/5.0 (iPad; CPU OS 16_6 like Mac OS X) AppleWebKit/605.1.15 (KHTML, like Gecko) Version/16.6 Mobile/15E148 Safari/604.1 - Google crawler User-Agent:

Mozilla/5.0 (compatible; Googlebot/2.1; +http://www.google.com/bot.html)

Over time, User-Agent strings have become bloated and inconsistent due to historical quirks and compatibility hacks. As a result, parsing them reliably often requires complex regular expressions.

However, this opens up a potential vulnerability: a maliciously crafted User-Agent string can cause regex engines to backtrack excessively, leading to denial-of-service (DoS) conditions such as stack overflows or system crashes.

Geo-IP is a technique used to map the incoming IP address of a request to geographical metadata—typically a country code, city name, or organization. This information helps identify traffic patterns and is widely used in observability dashboards, analytics, and request routing logic.

To enable this, proxies must load large Geo-IP datasets into memory and perform lookups on every request. Based on the result, the proxy may:

- Add dynamic headers (e.g.,

X-Country-Code) - Block traffic from specific countries, regions, or organizations

- Trigger geo-specific routing or responses

While powerful, this mechanism introduces additional memory and compute overhead to the proxy, especially at high throughput. Every request incurs a lookup cost, which can significantly impact resource usage and scalability.

This adds additional complexity to the system

Rewriting Paths

In many real-world scenarios, proxies need to rewrite incoming request paths before forwarding them to the upstream service. This can serve several purposes:

- Migrate /v1/* to /v2/*

- Redirect from HTTP to HTTPS

- Hide implementation details (/api/products?id=123 to /p/123)

This is where things like prefix stripping, redirects (301/302), or even full-blown regex rewrites come in.

Final Thoughts

While HTTP parsing might seem like a simple, “solved” problem, it’s actually where performance, security, correctness, and compatibility often collide. A reverse proxy acts as both a vigilant guard and a skilled translator, responsible for gracefully handling messy, unpredictable input. Understanding these complexities is essential for anyone building or operating scalable web services.

What’s Next

In future posts, we’ll explore how proxies tackle service discovery, load balancing, HTTP client behavior, and observability, and how these low-level responsibilities can ripple through the architecture of an entire distributed system

This post is part of a series.

Part 1 - A deep dive into connection management challenges.

Part 2 - The nuances of HTTP parsing and why it’s harder than it looks.

Part 3 - The intricacies of service discovery.

Part 4 - Why Load Balancing at Scale is Hard.